Editor's Choice

1850-1927

Hannah Phillips

Florence Nightingale's infernal machine

Handwritten Text Recognition technology means that the writings of Florence Nightingale and her correspondents digitised in this resource – both personal and professional – are easier to discover and navigate than ever before.

Handwritten Text Recognition technology means that the writings of Florence Nightingale and her correspondents digitised in this resource – both personal and professional – are easier to discover and navigate than ever before.

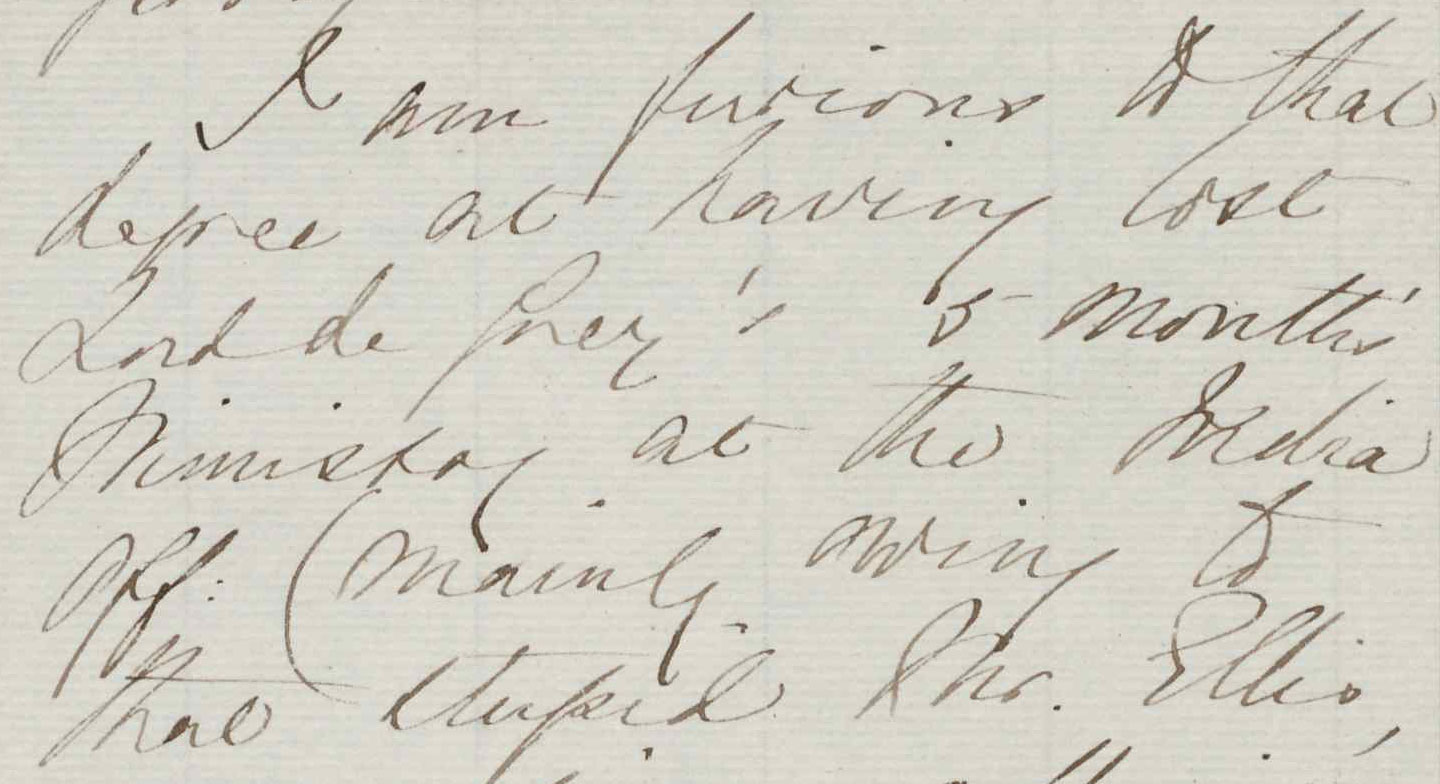

A personal highlight in the collection is the letter to Douglas Strutt Galton from 23 June 1866, that evinces not only a fascinating time in Nightingale’s life and work, but her engaging and indomitable attitude.

In the summer of 1866 Nightingale was at a high point in her renown; famous for her work in Scutari and publications including Notes on Nursing (1859). She had attended audiences with Queen Victoria and successfully lobbied for the creation of the Royal Commission. After moving to London, she focused her efforts on using this renown to instigate change, including improving sanitary conditions for soldiers and civilians in India under the British Raj.

Nightingale’s drive for change, however, often lead to frustration. After having lobbied for Lord de Grey to become the Secretary of State for India, hoping this connection would enable her to influence reform, he was in office for only five months before Lord Russell's Liberal government fell and he was replaced.

In this letter, after enquiring about future ministerial prospects, Nightingale expresses this frustration at the loss in her letter to Galton, and concludes in characteristic fashion: “I am fit to blow you all to pieces with an infernal machine of my own invention, which does me credit. Ever yours, F. Nightingale”.

You can search The Florence Nightingale Papers from the British Library using the interactive browsing tool, and search the text within each letter using the bar on the documents details page.

Matt Brand

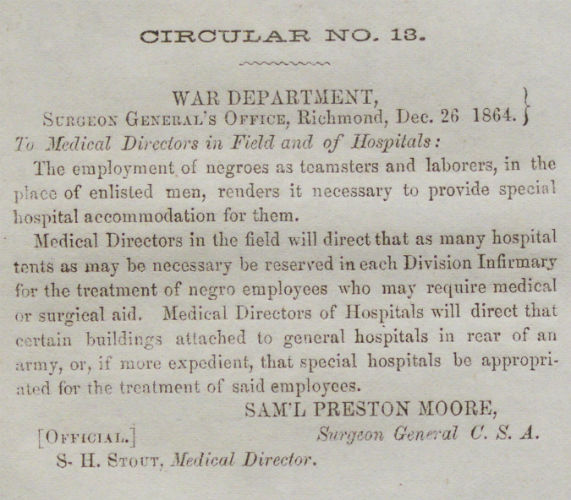

'The following paper is circulated for the information of the profession...'

Lindsay Gulliver

Women of the War

Barbara McLaren’s Women of the War (1918) shines a light on the heroics of doctors, nurses, policewomen, drivers, concert organisers and canteen workers who offered their services during a time of need. Celebrating women’s contributions throughout the First World War, the text was prefaced by former Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, who wrote: ‘They have done and are doing things which, before the war, most of us would have said were both foreign to their nature and beyond their physical capacity.’

Barbara McLaren’s Women of the War (1918) shines a light on the heroics of doctors, nurses, policewomen, drivers, concert organisers and canteen workers who offered their services during a time of need. Celebrating women’s contributions throughout the First World War, the text was prefaced by former Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, who wrote: ‘They have done and are doing things which, before the war, most of us would have said were both foreign to their nature and beyond their physical capacity.’

One woman chronicled early in the collection is Lady Paget. Having nursed throughout the Balkan conflicts of 1912 and 1913, Paget established a hospital unit in Serbia at the outbreak of war in 1914 and travelled to Uskub, where embattled troops faced a typhus epidemic. Evacuated after catching the disease herself, Paget later returned in the midst of an enemy invasion; during the occupation, 70,000 refugees were fed and clothed from her stores.

Another chapter focuses on noted ambulance drivers, Elsie Knocker and Mairi Chisolm. A decree forbade the presence of women on the front lines in March 1915, but ‘an exception was made for these two, mentioned by name’. Chisolm, at the time, was just eighteen years old.

Dr Elsie Inglis, meanwhile, is honoured for her role in originating the Scottish Women’s Hospital Units – ‘one of the noblest efforts achieved by women in the war.’ In the opening months of the conflict, the War Office refused the help of women’s hospitals, so Inglis – who had qualified as a surgeon in 1892 – offered her assistance elsewhere, establishing bases in France, Corsica, Macedonia, Romania and Russia.

After leading an ambulance unit, facing threats of execution and working under shellfire, Mrs. St. Clair Stobart was asked to mobilise a flying field hospital by Serbian authorities; she thus became the first woman to earn a rank – Major – in the Serbian army. After leading a column, intact, during the army’s infamously treacherous retreat, the chief officer of the Serbian medical staff would write; ‘You have made everybody believe that a woman can overcome and endure all the war difficulties’.

1928-1949

Rosie Perry

The National Health Service - Selling the Big Idea

The Beveridge Report, released in 1942, proposed social policy for the re-building of Britain after the Second World War. A key component of this report was the founding of a National Health Service, free at point of use and funded through taxation.

The National Health Service is now a source of pride for many in Britain, frequently ranking high in polls assessing what British people value.

However, the original proposals were not universally welcomed, facing challenges and criticism from MPs, Doctors and even the British Medical Association. Documents sourced from The National Archives, UK such as National Health Service: Individual Doctors. Representations (of which there are five volumes in this resource) contain correspondence, minutes and draft replies concerning the creation of the National Health Service, and the responses of doctors and their elected representatives to proposed schemes. Another volume, National Health Service Negotiating Committee (Medical Profession): British Medical Association concerns relations between the British government and professional associations.

The white paper A National Health Service was published in 1944 and detailed the war-time collation government’s vision for the NHS, to be the responsibility of the Health Minister. White Paper on a National Health Service: discussions between Minister and various interested bodies reveals notes for a speech given by then Health Minister in an effort to gain support for the proposals. He states “There is no reason nowadays why everyone should not be able to live with the complete assurance, at the back of his mind, that whatever he needs in the care of ill-health and help in good health will be there to his hand, as and when he wants its, for himself and his family, and that it is somebody’s job to see that it is there for him” and finishes by urging “I believe, quite frankly, that we are on the threshold here of the biggest single advance in the opportunity of health that this or any other country has had the opportunity of making. We want, and need, your help in making it.”

It wasn’t just the medical professionals that needed convincing. Aimed at the public, the film Your Very Good Health, was created by the Central Office of Information in 1948, explaining how the new state-funded National Health Service would operate and the benefits a free at the point of delivery health service would offer to everyone in England.

View all results for National Health Service here.

Matt Brand

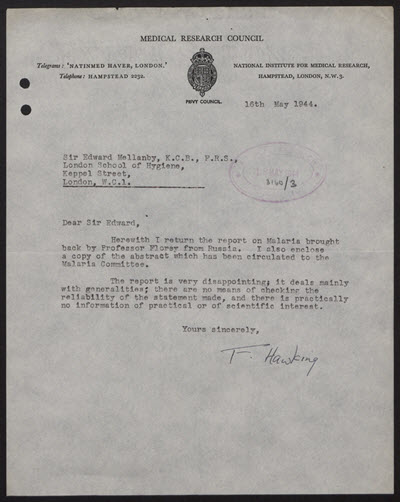

Dr Frank Hawking: like son, like father?

Whilst working on the second module of this project, I was pleasantly surprised to find out that among the many scientists whose name crops up was Frank Hawking (1905-1986), father of Stephen. The elder Hawking studied at Oxford University, and subsequently qualified as a medical doctor before pursuing a career as a research scientist.

Frank Hawking joined the Medical Research Council at the start of the Second World War, having returned to Britain from East Africa. Hawking spent the War serving on government committees which considered research into malaria, antibiotics, and tropical medicine, and applying himself to the important task of combating the spread of malaria among service personnel through new drugs such as mepacrine [atabrine], Paludrine [proguanil] and sulphonamides. The full scale of his wartime research can be surveyed in Medical Research in War: Report of the Medical Research Council for the years 1939-1945 (TNA FD 2/26), which describes the synthesis of Paludrine as ‘strategically decisive in the overthrow of Japan’, and records a trip to the United States to consider the work of American counterparts – a true mark of Hawking’s importance, considering wartime restrictions on official travel (pp. 62-63.) The list of wartime papers in which Hawking was the principal investigator (pp. 234-36) is truly impressive.

Hawking’s opinion appears to have been regularly sought by colleagues, and his minutes and correspondence give a sense of a man with a no-nonsense approach, perhaps even a dry sense of humour. Commenting on the dosage of anti-malarial drugs:

Russian research into his specialisation provoked a rather stronger response:‘Returned with thanks…

(1) 0.6g of mepacrine per week seems rather a high dose for seamen unless exposed to intense infection. 0.4g might probably be sufficient & cause fewer toxic reactions [.]

(2) The mepacrine should be taken each day under official supervision. Otherwise, much of the drug may not be taken.’ (TNA FD 1/6239)

‘Herewith I return the report on Malaria brought back by Professor Florey from Russia… [t]he report is very disappointing; it deals mainly with generalities; there are no means of checking the reliability of the statement made, and there is practically no information of practical or of scientific interest’. (TNA FD 1/6789)

And in recording what he apparently felt to be a case of stating the obvious:

‘During the period of January to March, experiments are greatly handicapped by the shortage of anopheline mosquitoes, which do not become really plentiful until June.’ (TNA FD 1/7047)

A pioneering scientist with a sense of humour. Wherever could his son have got the idea?

Rosie Burgoyne

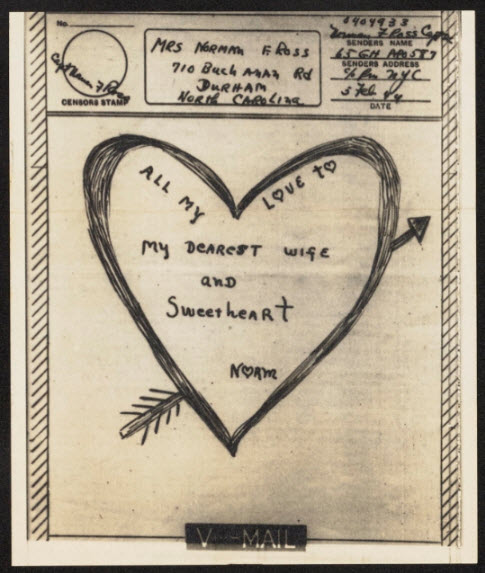

Wartime romance

The Norman Ross papers included in Medical Services offer a unique insight into the relationship between Captain Norman F. Ross and his wife Marjorie, offering personal glimpses into both Ross’s experience of the war whilst serving as a dentist with the 65th General Hospital and Air Corps Dentists, as well as his navigation of his relationship with his wife back home, which can be tracked through the letters that he sent her.

Whilst all of the letters are littered with romantic comments from Ross to his wife, by far my favourite has to be the playful valentine’s message Ross sent to Marjorie whilst he was serving overseas, in which he rhymes ‘ration’ with ‘passion’:

‘To my sweetheart

There ain’t no roses-

There ain’t no violets-

I ain’t got no sugar ration-

But for you I got plenty of passion’

Throughout the letters, Ross’s sense of humour shines through, such as in what he calls ‘a list you can show the mail man of all my wants’ which has his wife’s name at the top of the list, along with requests for her to send him nuts, sweets and paperback novels. (DUMCA MC 0001/007/002)

The war, however, remains a constant presence in the letters, with Ross writing that he ‘had a couple alerts and last night in the middle of the night things started popping.’ (DUMCA MC 0001/007/002) In another letter, Ross provides his immediate reaction to events the day after D-Day, writing that:

‘I sure am glad they finally got the power to get it started- I believe it will go on [through] now and shorten the war considerably. Sure do hope so cause I want to come home awfully bad, so I can love you.’ (DUMCA MC 0001/007/005)

Even so, Ross continues to remain hopeful about the end of the war throughout, going on to sign off the same letter with the touching words:

‘I love you, darling- I ache to get home – I try to ignore and forget the ache – but it won’t stay down – its especially bad to catch myself feeling sorry for me or bitter – that helps not a little teeny bit. But it will be over one of these days, darling. I love you – Norm’ (DUMCA MC 0001/007/018)

The letters in the Norman Ross collection in Medical Services are a fascinating feature of the resource, shining a light on the importance of the human side of the wartime medical efforts and providing an insight into the relationships between medical personnel serving abroad and their loved ones that were supporting them from afar.